Iceland. A fascinating, strange place. And misunderstood. Did you know that the famous Blue Lagoon is actually a man-made pool filled with runoff from the power plant next door? Or that Iceland could become the world’s next data center capital?

There’s something magical about a 2 a.m. stroll down Reykjavík’s party street watching burly dudes brawl under blue skies. But I’m not in Iceland to gawk, booze or hunt for trolls. I’m here because these guys really screwed up their economy a few years ago, and now they’re trying to fix it. And if all goes according to plan, the Internet is going to play a role.

Reykjavík isn’t a tech hub yet, but a lot of people are hoping that data centers can drive a nice chunk of its future growth. Moreover, if the promise of Iceland’s inexpensive, sustainable data center industry comes to life, it could accelerate the migration of all kinds of businesses into the cloud. That could be good news for thousands of Web companies and billions of users around the world.

Iceland’s Big Rebound

Iceland torpedoed its economy by playing way over its head in the global banking system. Legendary shenanigans, well worth reading about. Absurd deals, big cars, birthday-party-appearances-by-Elton-John kind of stuff.

Now, as Iceland rebuilds and stabilizes, part of its growth plan hinges on cooperation between Mother Nature and the Internet: low-cost, green data centers that are popping up outside Reykjavík, Iceland’s capital.

Iceland, where the dominant industries are fishing and aluminum smelting, has a few advantages that could eventually make it an important player in the massive and growing data center industry.

It’s Cheap Because It’s Green

The biggest costs of running data centers are electricity and electricity. Running the servers and keeping them from overheating consumes a lot of power.

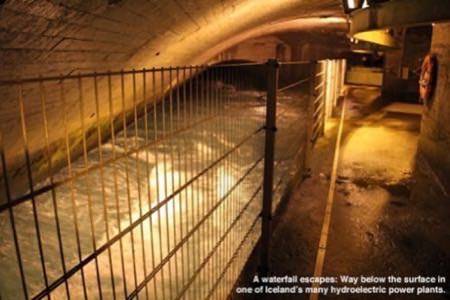

Lucky for Iceland, it has tons of electricity: inexpensive, practically 100%-green power generated by hydroelectric and geothermal plants around the country. Iceland generates more renewable energy per capita than any other country in Europe by far, the power company boasts.

As for cooling, well, it’s almost as simple as leaving the window open.

“This is a center-of-the-fairway, right-down-the-middle, perfect location for a data center,” says Tate Cantrell, chief technology officer for Verne Global, one of Iceland’s two main data center companies. (The competing Thor data center is across town.) “We wanted to anchor our company in a place where it just made 100% sense.”

Verne got the ball rolling in Iceland several years ago, and earlier this year, its first data center opened for business in an old NATO base, not far from Iceland’s Keflavík International Airport.

Welcome to the Rock

Inside, it looks pretty much like any other data center: clean floors, rows of server cages, neatly organized cables, LCD status monitors, gaseous fire suppression systems and the like – including laser air sensors that can “sniff” a server’s defective power supply days before it starts smoking.

The first working server room itself, made by a U.K. company called Colt, was constructed elsewhere and shipped to Iceland in container-sized “Lego blocks.” Verne can order them on-demand for relatively fast expansion.

But what makes Verne’s facility special – like other Icelandic data centers, now and in the future – is the way it’s run.

Thanks to all those hydroelectric and geothermal plants, the power is 100% renewable – no nuclear or coal. (There’s a diesel generator out back for emergencies.) This is nice for the planet, sure, and it may help some clients scratch the green itch. But it also makes running a data center super-affordable.

Iceland doesn’t have an easy way to ship its abundant electricity off the island, so it’s inexpensive if you can do something with it right there. Historically, that’s been aluminum smelting, which consumes some 70% of Iceland’s power. But most everyone is hoping that data centers take off. They’ll pay higher electricity rates, create better jobs and bring better visitors with them.

Cantrell shows me the Icelandic equivalent of a massive A/C unit: an opening in the wall that lets in the outside air but keeps out wind, rain and volcanic ash.

The air is monitored and circulated, of course. But even in late June, it’s chilly enough to cool the equipment without refrigeration. It’s actually mixed with warm, recirculated air to reach the target temperature. (In winter, Cantrell says, it never gets too cold – unlike, say, northern Sweden, where Facebook is setting up shop.) And that helps keep costs down even further. In Verne’s marketing materials, the company promises reduced cooling costs “by 80% or more.”

Verne doesn’t specify prices. But the point is that hosting in Iceland is designed to save a lot of money over markets like New York and London, where Verne will be looking to snag clients.

“In Manhattan, for example, based on our marketplace statistics, you’re going to pay around $500 per kilowatt of usable power,” says Jason Evans, CEO of Stackpop, an Internet infrastructure marketplace based in New York. “In Iceland, you’re going to pay slightly above $125 per kilowatt usable. Getting four times more power for your dollar for large server deployments could be enormous in terms of cost savings.”

Why Iceland Now?

So why isn’t Iceland a data center capital already? It has always been there, near the U.K. and a short flight from the East Coast. If you do business there, you get to go to Iceland “for work” whenever you want. Hello, Blue Lagoon and grilled lobster!

In the past the biggest hurdle was bandwidth: Iceland didn’t have the right underseas cables to support high-speed, low-latency data centers. Now it does, and new cables may eventually connect it with Canada, New York and Ireland, adding more capacity and quicker speeds. Today, a major U.S. or U.K. bank still isn’t going to house its trading servers in Iceland. But Cantrell estimates that an enterprise could host 75% or more of its applications at Verne, ranging from data analytics to email to backups.

Taxes were also a problem. Iceland stuck companies with a 25% tax on servers they brought in – a nonstarter that would have negated most cost savings. But the country’s parliament has resolved that issue: no more 25% tax.

Then there are Earth-related concerns. Will a volcano blow? Will an earthquake destroy everything? No, probably not. But Iceland is an island. You have to fly there – it’s not like taking a car from Manhattan to New Jersey. Add it all up, and no one has been fired for not betting on Iceland as a data center location.

After an official launch this spring, Verne’s server racks are starting to light up. Datapipe, a big hosting and colocation provider, is in. GreenQloud, a startup based in Reykjavík, offers Amazon-like cloud services hosted at Verne and Thor. CCP Games of EVE Online fame, founded in Reykjavík in the 1990s, is a Verne client. And Cantrell says a few potential European and North American customers were kicking the tires during my visit. No Facebooks or Googles, but that sort of thing takes time. Earlier this year, Bloomberg reported that Microsoft may be looking at Iceland.

The good news: Because Iceland is so small – and because the $100-plus billion global data center industry, per Gartner, is so huge – even modest success would make a meaningful change for the country.

The Verne campus might eventually top out at only 100 employees, Cantrell estimates. But “100 jobs are just great, really, for us,” says Magnús Orri Schram, a fast-rising member of Iceland’s parliament who played a role in getting the server tax taken care of. “We’re a very small community.” (So small, in fact, that Schram invited me to his house to chat on his sunny porch during his vacation. Great country!)

Iceland’s largest and state-owned power company, Landsvirkjun, hopes to command 1% of the European data center market by 2020. In terms of power consumption, that could amount to 1.5 terawatt hours, or about 10% of the energy Iceland generates today. So data centers wouldn’t be the biggest customers, for sure, but they would be important ones. And, again, they would be paying better rates – and creating better jobs – than the aluminum plants.

Remember, this is an island the size of Kentucky, with the population of St. Louis, in the middle of nowhere, coming back from financial collapse. Creating 100 jobs in Iceland is like creating 100,000 in the U.S. So if these data centers take off, they could be a great thing for Iceland.

And if it also means lower-cost and more sustainable service for Internet companies, and less strain on the planet, it’s an easy win-win-win.